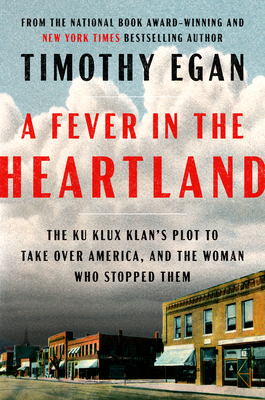

A Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them (2023) by Timothy Egan is described as a “historical thriller” and that is true–I couldn’t stop listening to it at every opportunity, even though I knew the outcome. What is most horrifying is that it is a completely true story, and it happened in my home state of Indiana only a hundred years ago. Bear with me, as this is a little different than my usual review. There is no anti-fatness here, but there is a lot of racism, sexism, and religious and ethnic discrimination that was endemic at the time, described in this important book.

I vaguely knew something of the story from reading the short story “Night Train” in Susan Neville’s short story collection In the House of the Blue Lights, years ago. But whether you read Neville’s short fictionalized version or Egan’s exhaustively-researched book, the facts remain that D.C. Stephenson came to Indiana with the purpose of resurrecting the Klan here in the 1920s, and succeeded, taking over all statewide and most local political offices. He would have continued, until in his many abuses of power, he assaulted and raped Madge Oberholtzer, a secretary, who tried to kill herself afterwards, but survived for weeks, during which time her supportive and heartbroken family worked with a lawyer for Madge to make a dying declaration, which was used during Stephenson’s trial to convict him and send him to jail. I was horrified, sad, and angry as I read how it all happened. Why were so many white men and women taken in by this message of hate, led by a man who bragged that he “was the law” who was a serial abuser and rapist? As I write this, I realize the question is still relevant today.

After Stephenson was imprisoned, the Klan’s hold on Indiana politics was loosened somewhat. But I grew up in northwest Indiana and have spent the past 18 years in the Indianapolis area as an adult. I don’t think the attitudes that allowed the Klan to take hold here a hundred years ago have changed enough. We have a long way to go.

Egan’s book really made me think about my own family history and what part my family played. Half of my family, through my mother, were Polish Catholic immigrants in northwest Indiana, targets of the Klan. My father’s mother also grew up in northwest/north central Indiana in a Jewish immigrant family, in the 1920s. From the historical research I’ve done, she was the only Jewish student in her high school class of about 30 students. She was supposed to go to college, but instead married my grandfather, a festival “carnie,” in 1933 when she was 18. He had been raised in west central Indiana, was a white Protestant, and and I continue to hope that he was too young to have been caught up in the fever that Egan describes, as he would have been only 13 or 14 during the events of the book. But he had several older brothers who would have been young men then, who I assume had probably had been card-carrying members, as Egan wrote in A Fever that “in 1925, if you were not a knight of the KKK, you did not belong.”

I wonder what my grandmother read in the newspapers as a young girl of 10, in 1925, when this happened, and thereafter? What experience did she and her family, as Jewish immigrants, have with the Klan? I had always wondered why she assimilated, why she married my grandfather, why she didn’t raise her own family in the Jewish faith? After reading A Fever in the Heartland, I have some ideas. And I went to visit Madge Oberholtzer’s grave, which I found out after reading A Fever in the Heartland is located not very far away.

Everyone should read this important book so we can avoid it happening again.

it’s sounds like an interesting read. I will look it up!

LikeLiked by 1 person